Photograph by Jens Umbach

It arrives with a shock, probably like a jellyfish sting in ankle-deep water — INSUFFICIENT FARE.

And then one hundred and four dollars are ripped from my pocket. That’s how the worst day of the month begins.

My plan is to bike in to the studio every day, once the weather becomes dependably warm. And then do my best to avoid the trains until November. If I have a meeting, I’ll bring a change of clothes and wash up at work.

But this price point — it’s vile. An almost 20% fare increase with a 0% improvement in product. In particular for those of us that live on the C.

The full-car adverts the MTA runs to rationalize the change only serve to amplify my frustration. Their only advertisement is their product, and right now their product is eighties-vintage C trains and unmanned token booths.

I’m writing this on a train home, at the end of a deeply exhilarating, deeply exhausting day. I worked late because meetings ate the day, and so am riding home with everyone else that works their ass off to survive in this city. Everyone looks tired, ready for the comforts of home. Black, White, Asian, Hispanic, old, young…this is New York. But the majority don’t have my luxury: self-employment, no dress code.

What happens when the fare becomes $150? $200? What resistance can we offer that? How to keep the plutocrats from pouring our money down the bottomless maws of corruption and inefficiency?

I’m going to give this some thought. New York deserves better.

The boy is now five. A major part of the year ahead, we agreed, is reading. I’ve been ready for this moment for years.

The course charted by our society is often powerfully alien to me.

I’m thinking about this because I’m thinking about 22 year-olds going on murderous rampages. Throughout history, every injustice has been paired with a justification; I’m intensely curious to see what explanations are ultimately made for last Saturday’s violence. But when I consider Jared Lee Loughner, and the world he was brought up in, there’s no running from the fact that it’s the same world my son lives in.

It’s old news that America is an incredibly violent place. Nudity offends the senses here more than images of weaponry. The iconography of war is mainly interpreted as energy, and possession of military-grade firearms is defended as a right.

See Football, America’s primary diversion (now entering it’s seasonal crescendo). Gladiatorial arenas, domination by force and amplified collisions via armor that allows one to (finally?) act with abandon. See the fervor of the need to dominate the competition.

See the way that America’s television news media covers war, or heralds the approach of any armed conflict. A 24-hour news cycle would, on paper, suggest the availability of time for a thoughtful consideration of all things. Instead we have countdown clocks, explosive motion graphics, and experts paid to speak excitedly of the “inevitability” of war.

See movie posters, even if you can’t stomach the movies themselves. I ride the subway to work daily, and I always examine the underlying forms of the large-format imagery that cover the passing stations. More often than not, I’m looking at a gun, am looking at a gun pointed at me, or am being asked to admire the weaponry carried by any of a long line of heroes.

See videogames. Of course, there are many genres, but high atop sales charts are hyper-real, first-person, deeply immersive, incredibly violent shooters. Many of these feature intricately woven narratives and truly brilliant storytelling, with visuals and audio to rival mainstream cinema. That this is the primary distillation of an art form that I regard as one of our society’s most promising, and potent, is telling unto itself.

See comic books, perhaps our most powerful communication art. Relegated to a cultural ghetto on account of the power fantasies that always drove commercial success, American comics have been aimed at adolescent boys for decades. Drama and violence proceed there on epic scales, thanks to the unlimited special effects budget brought to bear by the imaginations we all carry.

My son will be 5 in three weeks, and he knows that Wolverine has claws. Though I own many comic books, and look forward to sharing their content with him as he matures, I’ve not yet read any of them to him.

I can see too clearly the fabric of the world when I observe its texture reflected in my son’s eyes. There’s information that’s readily available to those that seek it. It’s in the air, the water, the culture; there’s no running from we’ve allowed to be created. I look into Jared Loughner’s eyes, and this much is clear.

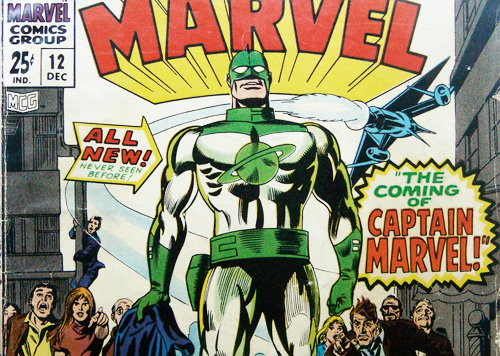

Marvel Super-Heroes #12, 1967

I was always a Marvel guy.

In the beginning, it wasn’t entirely by choice. Marvel Comics were simply what the neighborhood stationary store chose to stock. Picture a rickety, rotating wire tower filled with whatever publications a disinterested Korean store owner in Queens might select for display in the early eighties. Mad Magazine and Archie Comics may have been my other options.

The specifics are now lost to time, but it probably started with the Claremont / Byrne X-Men, luckily enough. Comic books were a major part of my childhood for as long as I can remember having one, and the storylines those men were putting out in their prime were more than sufficient to wrap a casual buyer in profoundly. Given the complexity of the writing, my reading sophistication steadily grew to allow an appreciation of the subtext below the supernormal, and it would guide my subsequent collection choices.

In time, I began to recognize the special appeal of the world that Stan Lee and Jack Kirby had built: the inhabitants of this amazing place were always people first, fantastical constructions second. For all that they could do, they were forever bound by what they could not. This conflict, Stan and Jack knew, is what creates genuine drama, and it pervades all of Marvel’s greatest creations.

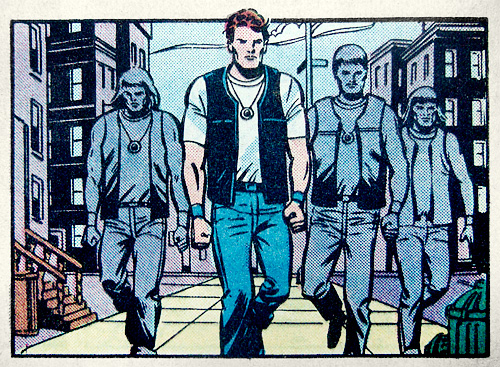

Marvel Saga #1, 1985

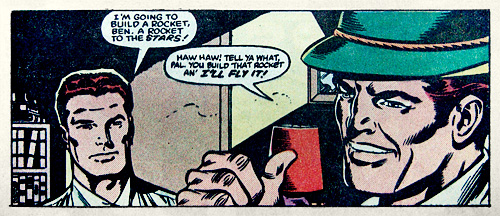

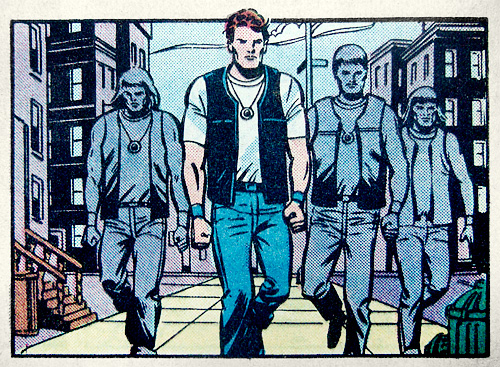

Consider the story of Benjamin J. Grimm. A scholarship athlete who narrowly escaped the rough-and-tumble of Yancey Street, he had a special skill with airplanes. The faster, and more experimental, the better. Years after their meeting, when Reed Richards developed an extremely experimental faster-than-light drive, the only pilot he’d consider for the job would be his close friend (and former college roommate) Ben Grimm.

Marvel Saga #1, 1985

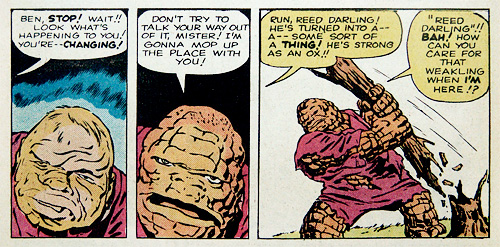

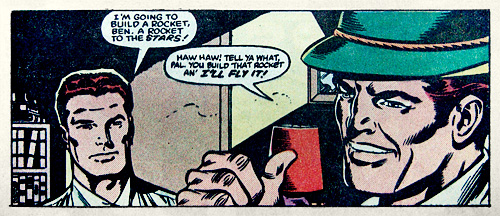

Barely out of earth’s atmosphere, a massive cosmic ray storm assaulted the spacecraft, forcing the crew to abort the flight. The autopilot systems guided the craft earthward to safety, but when the four emerged from the wreckage, they each found themselves dramatically changed—none more so than Ben.

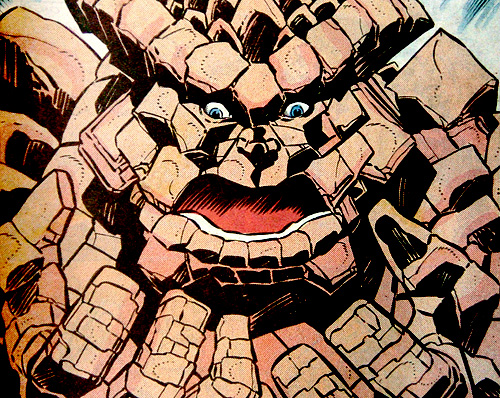

Fantastic Four #1, 1961

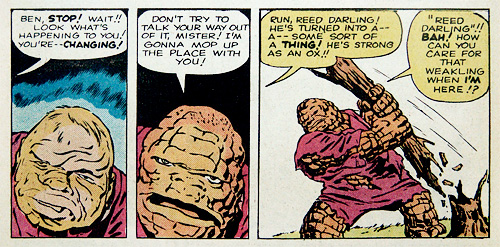

He’d mutated into a massively powerful, orange, misshapen…Thing. But, somehow, this transformation into a bulletproof, lumbering behemoth served only to underscore the quality of his soul. For all the change wrought to his exterior, what hadn’t changed were those baby blue eyes, and the contrast worked to reveal the heart that had always shined so brightly within them.

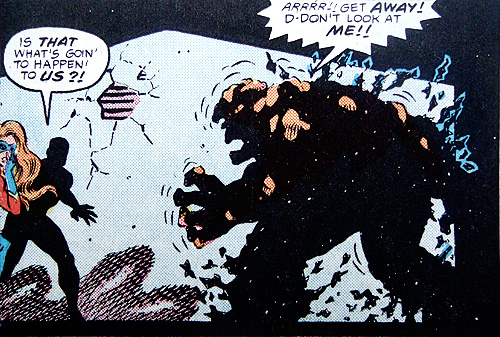

Marvel Saga #1, 1985

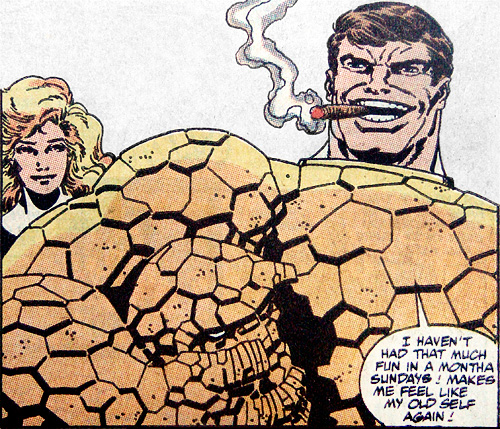

Despite the ongoing pain and humiliation that came from his transformation, Ben would gain celebrity and respect for his exploits as a founding member of The Fantastic Four. The foursome would go on to save the world more times than anyone could count, and though he’d always yearn for a chance to simply be human again, Ben would find a version of happiness, purpose and stability in his new life as a superhero.

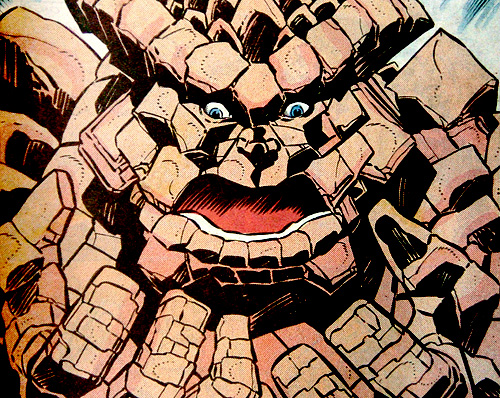

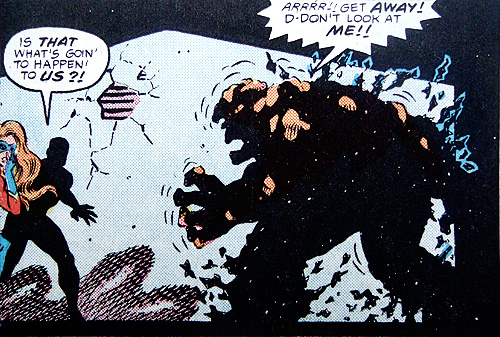

The Thing #25, 1984

But the stability would never last long. With the resilience of character shown through the trials he’d endured from creation, any writer worth his salt knew that Ben Grimm was the very definition of drama, of conflict.

The Thing #36, 1986

If he were ever to grow too comfortable in his own skin, the inertia would drag his character down into a puddle of self-loathing. Change could be internal or external, but change had to be the Thing’s only constant.

Fantastic Four #310, 1988

As it will be with this edition of superbiate.com.

A site that once existed only to showcase my commercial photography is now reborn as a workshop of ideas. I expect this space to go through many mutations (both internal and external) as I explore this still-young communication medium.

In large part because I do so much more than take pictures these days. Superbiate & Son has gone completely unedited since the fall of 2008, when I began the business of founding The Vanderbilt Republic. Creating that company has been a process akin to exploring the contours of my own soul (in public). It’s been a messy, glorious, insane, inspired time. And I now know how Reed Richards felt when he emerged from the wreckage of a spacecraft, saw his three dearest friends transform dramatically, and felt the first tingle of cosmic rays in his bones.

I haven’t the slightest idea why I’m still standing, what my power will be, or what the future holds. But I do know that I’ve survived more than most could ever expect to, and that in itself ain’t half bad.

Fantastic Four #336, 1990